Dr. Vincent Lam is an addiction-medicine physician, and the medical director of the Coderix Medical Clinic. He is a Giller Prize-winning author whose latest novel, On The Ravine, explores Canada’s opioid crisis.

As an addiction doctor amid a continent-wide opioid crisis, I am often asked of drug and alcohol addiction: “Can it even be treated?” and “Do people with addiction actually get better?”

My answers are emphatic: Yes, there are good treatments. People can recover. Previously, when I was an emergency physician, no one ever asked me whether it was possible to mend a broken bone or treat a heart attack. We are fortunate in the 21st century to correctly assume there are effective treatments for many conditions. Yet, addiction is often viewed differently. People with a substance use disorder are also viewed differently. While popular culture celebrates people who have overcome serious illness to run marathons, go back to work, or otherwise return to vitality, many lay people, as well as health professionals, assume that people with an addiction are “lost” to society and the economy.

Once I have explained that treatment exists and people can recover, I am sometimes asked: “Why is it still such a problem?” and “What can we do to fix it?” Often, reference is made to those who are unhoused and visibly unwell on our streets. Although important, this asks only half the question. On its own, it frames people experiencing addiction as “broken,” primarily in need of an outside “repair.” Certainly, high-quality health care must be provided. But people who thrive in recovery do so as active participants in their own life, not simply as passive recipients of health care. People flourish when they can imagine their life changing for the better and can access opportunities that allow constructive action. Improving one’s life entails building a structure of meaningful relationships and routines, in which work usually plays a part.

Rather than being broken and in need of repair, I think that some of my patients are stuck. I hope that my care will support them, but much needs to happen outside of my clinic for them to become unstuck. At a national level, can we create opportunities for lots of people to get unstuck? I think we can. Recently, the federal government created the Major Projects Office and Build Canada Homes. Through these agencies, we have a strategic opportunity to help Canadians get unstuck from the continuing opioid crisis as well as other addictions, and to move their lives forward and participate in Canada’s economic renewal.

The staggering productivity cost of a human tragedy

Jonah Atkins/The Globe and Mail

Addiction ravages every aspect of a life. For many people, by the time they seek my help, the trust of loved ones has been compromised, finances have been gutted and employment has been lost. While headlines about the opioid crisis rightly highlight the tragedy of 53,308 apparent opioid toxicity deaths between January, 2016, and June, 2025, many people with an addiction live a daily tragedy in which loss of work, income and human connections spirals into a loss of purpose, housing, dignity and options. Treatment and harm reduction may be contributing to an opioid toxicity death rate that fell 22 per cent in the period of July, 2024, to June, 2025, compared with the previous year, but it is difficult to reach a firm conclusion, as other variables are also at work. Meanwhile, this reduction still amounts to 17 deaths per day, which are preventable and unacceptable.

Beyond these numbers, the stereotype of a person struggling with addiction is that they are unhoused, unkempt and have nothing to offer society. Many would be surprised to learn that my patients include physicians, educators, artists, business leaders and workers of every type. Of those who died from opioid overdoses between 2016 and 2021, more than two-thirds were employed within the five years prior to their deaths. The estimated productivity loss of those deaths was $8.8-billion. The Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction found that in 2020 alone, lost productivity costs attributable to use of substances, including drugs, alcohol and tobacco, was $22.4-billion, while premature deaths attributable to opioids resulted in the loss of 112,768 potential years of productive life. That is a staggering productivity cost as well as a human tragedy.

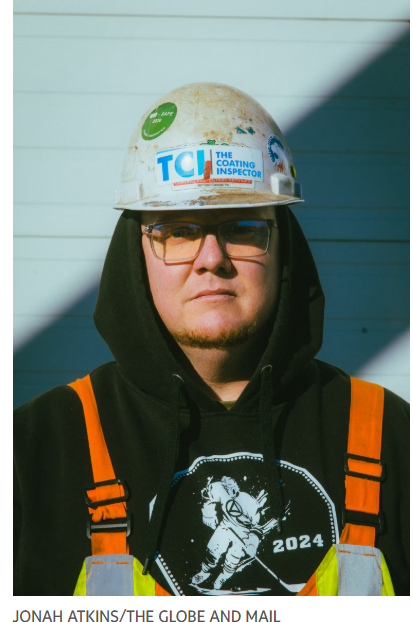

Most over-represented in my waiting room are tradespeople. The skilled workers in my practice include carpenters, roofers, plumbers and machine operators, to name a few. One story I hear all too often is that a worker suffered a painful injury, it was difficult to access physiotherapy or take time off work to recover, or they could not find a work role that did not exacerbate their injury. They were prescribed opioid medications that masked the pain, and they became addicted. Others developed their addiction outside of work and tell me of a work culture that normalized substance use. These individual stories form a larger picture, in which three out of four opioid-related deaths in Canada since 2016 were in men, and of those men who were employed at the time of their deaths, between 30 and 50 per cent worked in trades.

Our primary medical response must be to implement the strongest recommendation of the National Opioid Use Disorder Guideline, which is to provide medical treatment with Opioid Agonist Therapy (OAT). Long-acting opioids used in OAT – primarily methadone and buprenorphine – reduce the risk of mortality, and stop the roller coaster of ups and downs which come from the effect of short-acting opioids and then crippling withdrawal.

Another important health care response is harm reduction, providing easy access to the overdose-reversal medication naloxone, supervised spaces to use drugs, clean drug-use supplies that reduce the risk of infection, and a pathway to treatment. These services should not be the end point, rather they should be a basic starting point from which we ask: “How do we support people to get unstuck?”

People who are unhoused need to become housed. People need human relationships and sources of enjoyment outside the world of drug use. People need daily routine and purpose, typically found through work. Some of my patients assemble these ingredients themselves, often when fortunate enough to be supported by family and friends. By chance, some of my patients in the trades find a co-worker who has themselves overcome addiction and acts as an informal sponsor and workplace mentor. But for many without these ingredients, even if their medical treatment is optimized, they remain marginalized, isolated, dissatisfied and at prime risk for relapse. They are not thriving. They may have great medical treatment but are still stuck.

Is there an example of a system that puts in place the ingredients for people getting unstuck, successfully supporting them on a pathway forward? There is. Part of my practice is that I care for health professionals who experience addiction, and who participate in either Ontario’s Physician Health Program, or its Nurses’ Health Program. Other Canadian provinces have similar programs.

A health professional typically finds their way to me when their work has been compromised due to their addiction. Often, their professional licence has been suspended. Despite confronting a potent mix of shame and fear for their future, health professionals can access a clear pathway to recover from addiction, return to work they care about and continue to be valued members of their community.

The scope of these programs is comprehensive, and includes co-ordinating and overseeing an independent medical examination, ongoing medical treatment, recommendations to licensing bodies, individualized return to work plans, as well as workplace support. Participants sign a monitoring agreement which stipulates complete abstinence from drugs and alcohol and monitoring of this abstinence with urine and potentially other testing, typically for five years. They commit to following medical treatment recommendations, participating in peer support groups called Caduceus Groups, and regular meetings with a case manager as a condition of being able to work in health care.

In a study of a similar program in the U.S., the monitoring agreement was highlighted by participants as being helpful. These programs succeed by linking addiction treatment and work, with the crucial ethos towards participants that theyhave a valuable contribution to make to society and the program has dual goals of both supporting the person and their contribution. In Ontario, 85 per cent of physicians in the Physician Health Program complete it successfully, and at the end of a five-year program they can practice medicine without additional oversight.

Available statistics show that in 2021, more than 1.6 million tradespeople were employed in Canada, while in 2022 we had more than 96,000 doctors, and in 2023 we had more than 300,000 registered nurses. With roughly four times the number of tradespeople as doctors and nurses combined, shouldn’t trades workers be able to access the same kind of high-quality support program as health care professionals to recover from addiction and return to a productive career?

Instead, a 2024 study by CUPE identified a lack of awareness amongst tradespeople regarding available services and treatments, and identified a need for a “holistic suite of services and clearer pathways to work.” It surveyed workers and apprentices in the trades and found that 20 per cent indicated that at some point in their life they felt they needed professional help to deal with a substance-related issue, but only about half received that help.

Responding to the statement “I would not know where to turn for help,” 37 per cent of respondents felt this was either completely true or somewhat true for themselves. Opioid pain relievers were used by 10 per cent of respondents within the previous 12 months. Of this group, 39 per cent were using them without a prescription or differently than prescribed. Other substances also impact people in the trades, where 59 per cent of respondents in this survey reported consuming alcohol excessively within the past 12 months, and the rate of stimulant use was higher than the general population. This report observed that “the prevention, management, and treatment of substance use, is vital to ensuring the continued success of the skilled trades,” noting a climate of labour shortage, impending retirement of older workers and a high rate of apprentices not earning their certifications.

To look at the high rates of substance use in the trades is not to cast judgment upon those who work in this field. It is to recognize that this is an area of work where in addition to the physical risks and mental stress of difficult physical labour, workers are subject to an elevated risk of developing substance use disorders. This risk must be met with support.

We can support addiction recovery and return to work

Jonah Atkins/The Globe and Mail

The Major Projects Office and Build Canada Homes should play a central role not only in catalyzing economic opportunity for the country, but in providing opportunity for tradespeople who are in recovery from a substance use disorder, and can offer a great deal to Canada’s economic recovery. The ambitions of these programs need workers to be realized. By 2032, Canada will face a projected shortfall of more than 61,400 construction workers. By 2033, there will be an estimated 410,000 job openings in the skilled trades.

In collaboration with ministries of health across the country and Employment and Social Development Canada, a “Trades Health Program” should be created. Analogous to our health professional programs, it should support tradespeople who face substance-related and mental-health issues by co-ordinating health care services, providing monitoring and reintegrating workers.

Some might ask: Shouldn’t we “fix” people first and then return them to the workplace? While it is true that sometimes a period of intensive treatment without work is important to stabilize people with addiction, a key lesson from the successful programs we have for health care professionals is that a longitudinal approach that links addiction treatment to ongoing support and monitoring in the workplace promotes sustained recovery.

“I was dying and I was helped, and now I need to help people.”

– Scott Menzies, founder of Hard Hats, in an interview for The

Globe and Mail’s Poisoned series.

Education and peer support are key parts of a comprehensive approach to caring for workers and should be vital partners, but these are not the whole solution. A Trades Health Program would liaise with unions, provincial workplace compensation boards and employers. Eventually it would be ideal if the Trades Health Program were available to any trades worker in Canada, but the place to start is where the public is already making a significant new investment and the federal government can act directly – through projects of the Major Projects Office and Build Canada Homes. We can no longer tolerate a situation wherein we have unhoused people who have the skills to build the homes we all need. We know how to support both their addiction recovery and their return to work.

Primary prevention is also crucial. North America’s history of opioid over-prescribing has contributed to our standout tragedy, with our far higher rate of opioid-related deaths than the rest of the world. The Center for Construction Research and Training recommends that “one important way to reduce rates of opioid use disorder is through primary prevention strategies that reduce the likelihood that workers in the construction industry get injured or, if injured, are prescribed opioids when effective non-opioid treatment options are available.” The Major Projects Office and Build Canada Homes should ensure best workplace safety practices in their projects to reduce the risk of injury. It should be in dialogue with provincial workers’ compensation boards to ensure that opioid-sparing treatment options are always fully considered for injured workers, with robust support of physiotherapy and occupational therapy options.

Expanding Bill C-64, the Pharmacare Act, to cover methadone and buprenorphine, the main treatments for opioid use disorder, is also key. Too often, I have patients who want to return to work, but coverage for their essential medication is tied to a provincial welfare or disability program. They cannot take an entry-level job lacking benefits because they cannot afford their medication on that wage, so they are forced to remain on a public support program. For most people, OAT is a chronic treatment akin to a blood pressure or cholesterol medication. For those who wish to stop it, the medication should be tapered very slowly, because abrupt discontinuation results in terrible physical symptoms of withdrawal and high risk of relapse. This process can easily take a year or more. The Canadian economy is robbed of a productive worker if someone is kept tied to a provincial income support program because that is the only way for them receive their essential medications.

There is no single magic solution to the multifactorial problem of the opioid crisis, and a Trades Health Program is not the solution for everyone. Some people are not trades workers, and some trades workers with a substance use disorder may not be ready for a program like this. We have other challenges to address: although we know that OAT is crucial, access remains inconsistent. People need to be able to easily obtain their medications in order to benefit from them, but some pharmacies don’t stock OAT. Some communities and hospitals don’t have addiction doctors. Stigma is rampant, and often results in people with addiction receiving poor health care for both addiction and non-addiction related issues. All this needs to change. Harm reduction remains crucial, as a strategy that meets people where they’reat, and links them to treatment.

However, the risk in saying that a problem is multifactorial is that people feel that the problem is too big, and too complex for anything to be done about it. There is a great deal we can do. We should learn from existing models that work, and find synergistic, practical solutions. There is clear synergy between supporting meaningful and robust addiction recovery for trades workers with addictions, and the aims of the Major Projects Office and Build Canada Homes. As we are embarking on a national project to revitalize the economy with major infrastructure and housing spending, we must engage workers in this country who have been sidelined by the opioid crisis and other substance use disorders.

People who have struggled with substances don’t only want to hear “What services can we offer to you?” They want to be seen for their value, skills, and humanity, and for what they can offer to the prosperity and future of Canada.

Article By: Jonah Atkins/The Globe and Mail