It’s our pleasure to feature from our archives Nancy Duxbury’s introduction to a collection of essays on artistic animation. Our research group’s collaboration with the University of Coimbra began in earnest shortly after the completion of our SSHRC-funded community-university research alliance (CURA), Mapping the Culture of Small Cities, extending our work through conference participation and co-publication. Our current focus on community and cultural mapping emerged from shared interests and research partnerships first developed via the CURA and via the remarkable collaboration led by Duxbury and her colleagues. The following “Introduction” documents the early days (and potential) of that collaboration.

First published in Nancy Duxbury (Ed.) Animation of Public Space through The Arts: Towards More Sustainable Communities. University of Coimbra Press, 2013.

INTRODUCTION: FROM ‘ART IN THE STREET’ TO BUILDING

MORE SUSTAINABLE COMMUNITIES

Nancy Duxbury

Centre for Social Studies, University of Coimbra, Portugal

How can innovative artistic animation of public spaces contribute to building more sustainable cities? This was the question originally posed to participants in the international symposium “Animation of Public Space through the Arts: Innovation and Sustainability,” organized by the Centre for Social Studies at the University of Coimbra, in Coimbra, Portugal, September 27-30, 2011. The international symposium was inspired by the growing need of communities to deal with complex issues intertwining multiple dimensions of environmental, cultural, social, and economic sustainability and resiliency. In our cities, both large and small, numerous processes of change and adaptation are underway. These Processes must be underlined by wide public participation in the development of new alternatives and new social institutions to manage processes of social life. Artistic practices, interventions in shared public space, and public engagement strategies can play significant roles in both illuminating and effecting positive cultural changes and can help to catalyze public participation in the urgent task of transforming our cities and communities into more sustainable places.

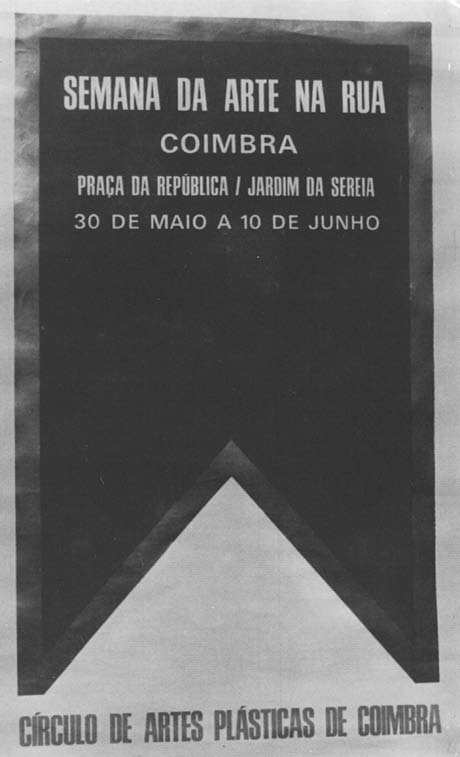

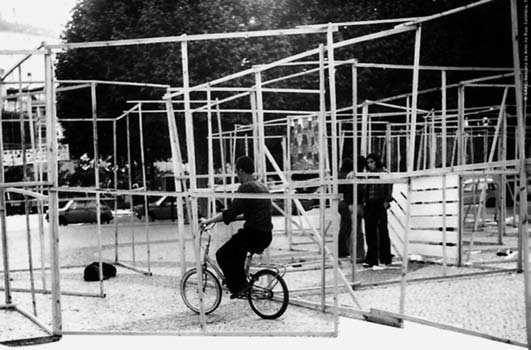

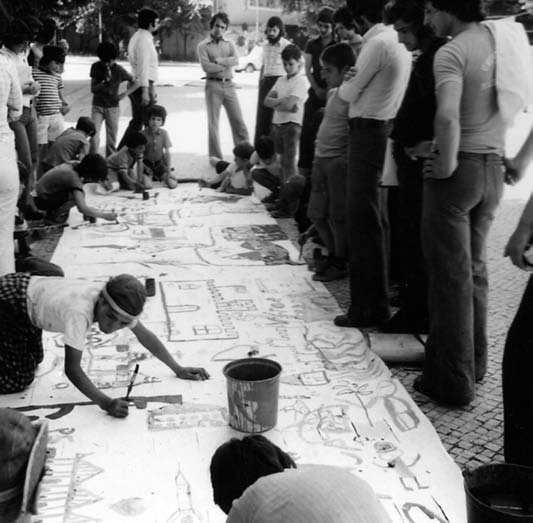

The setting of the event in Coimbra was significant. The animation of public space in Coimbra through artistic interventions and activities has a long history, linked both to its lively student body and its vibrant artistic scenes. Of particular note, Coimbra’s ‘Semana da Arte na Rua’ (‘Week of Art in the Street’), held from May 30 to June 10, 1976, in the early post-revolution years, brought a ‘critical mass’ of multiple artistic interventions in the public spaces of the city (Figure 1). The event celebrated freedom and art as a way of assembling people. Praça da República became a big maze where visual artists could hang their paintings, and artisans could hang tapestries and other artifacts, forming a kind of communion between art and popular culture. Organized by artists of the Círculo de Artes Plásticas de Coimbra, the site’s animation involved the participation of contemporary artists and traditional artisans, amateur theatre makers and musicians, and avant-garde musicians (see Figures 2 and 3). It was also then that GICAP (Group of Intervention of Círculo de Artes Plásticas) was formed, a performance art group that dealt with the relationships between the collective and the individual. For example, during the ‘Week of Art in the Streets,’ the artists of this group made clothes that were ‘wearable paintings,’ bringing closer the artist, the body of the artist, and his/her creations (Figure 4). The symposium celebrated these actions and added a new spin, focusing on contemporary issues of societal change within the context of local sustainability.

Photo © CAPC.

Photo © CAPC.

The symposium promoted interdisciplinary knowledge exchanges and highlighted practice-led research related to sustainable city-building and the animation of public space. It involved architects, theatre makers, community-engaged artists, urban developers, researchers in many disciplines, and university teachers and students. Geographically, the event brought together presenters from Europe (Bulgaria, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom), North America (Canada and the United States), South America (Brazil), and the Pacific (Australia and New Zealand). Participants shared a common interest: to explore the multifaceted and increasingly vital connections among place, space, community, arts, animation, public engagement, and sustainability.

To further encourage practice-based knowledge exchange and interaction, the symposium was accompanied by two full-day workshops on theatre interventions in public space and cultural mapping and a five-day student theatre workshop/exchange. In these workshops, artists, architects, teachers, researchers, and students worked together to share expertise and pursue experimental actions in various public spaces around Coimbra.

The overall series of events was organized by the Centre for Social Studies at the University of Coimbra and realized through a number of international collaborations and local partnerships. The Small Cities Community -University Research Alliance at Thompson Rivers University, Canada, co -organized the Cultural Mapping Workshop, ‘Exploring Connections among Place, Creativity and Culture’. The Utrecht School for the Arts, The Netherlands, and O Teatrão, Coimbra, co -organized the Theatre Workshop ‘Animation of Public Spaces through Innovative Artistic Practices’. The Students’ Theatre Workshop/Exchange, ‘Animation of Public Space: Artistic Intervention Experiments to Encourage Audiences to Co -Own Public Space in a Sustainable Way’, was co -organized by the Utrecht School for the Arts, O Teatrão, and Stut Theatre (Utrecht). The European Network of Cultural Administration Training Centres (ENCATC) thematic area on ‘Urban Management and Cultural Policy of the City’ and the University of Coimbra’s ‘Cities and Urban Cultures’ MA and PhD programs and Department of Architecture also contributed to the development of the event.

We greatly appreciate and acknowledge the inancial support received fromthe Portugal Foundation of Science and Technology (Fundação para a Ciéncia e a Tecnologia – FCT) and the Embassy of the Netherlands in Portugal for the event. In addition, venues were generously provided by Mosteiro de Santa-Clara -a -Velha de Coimbra (Direcção Regional de Cultura do Centro), Museu da Água Coimbra (Águas de Coimbra), and Circulo de Artes Plásticas de Coimbra (CAPC). The production of this book was possible through support from the Portugal Foundation of Science and Technology as well as Textual Studies in Canada and the Small Cities Community-University Research Alliance, both based at Thompson Rivers University, Canada.

Following the symposium, papers were reviewed by an editorial review committee consisting of Nelly van der Geest, Utrecht School for the Arts, The Netherlands; and W.F. Garrett -Petts and James Hofman, Thompson Rivers University, Canada. Selected papers were consequently revised for publication. Thank you to the members of the editorial review committee for your advice and guidance, and to all the authors for the knowledge, insights, and inspiration you contribute to this collection.

In this volume, sustainability is deined holistically, keeping in mind the interconnected dimensions of environmental responsibility, economic health, social equity, and cultural vitality (Hawkes, 2001), and stressing the necessary integration of these domains into a holistic approach toward local development. As Choe, Marcotullio, and Piracha (2007) express it, “Culture in sustainable development is ultimately about the need to advance development in ways that allow human groups to live together better, without losing their identity and sense of community, and without betraying their heritage, while improving the quality of life” (p. 202). Also critical is the local capacity for resilience, described by Allegretti, Barca, and Fernandes (this volume) as “a capacity to adapt to transformations of external conditions in the urban panorama.” Incorporating artistic approaches and cultural considerations into our thinking and planning for greater local sustainability and resiliency is an emerging practice characterized by numerous experiments and the gradual rise of trans- -local knowledge -sharing and co -learning networks.

Issues of sustainability and resiliency are at the forefront of public agendas internationally – from cities and communities to global policy fora. Although precise conceptualizations of the ‘sustainable city’ are “rare and contested” (Williams, 2010: 129), it has become the dominant planning and policy paradigm in which the place of culture is being discussed and assessed. The fourth pillar of sustainability – culture – has gradually become more recognized in policy and planning (see, for instance, UCLG, 2010; UNESCO’s Hangzhou Declaration, 2013), but understanding its role in a sustainability context remains challenging both conceptually and in practice (see Duxbury, Cullen, and Pascual, 2012; Duxbury and Jeannotte, 2012). Further evidence is needed on how artistic practices contribute to the societal transitions required to build more holistically sustainable and resilient communities. In this pursuit, the direct experiences and insights from artists and others working with artistic processes in the public realm and with various publics on issues of socio- -cultural and community change, (re)attachment to place and environment, and re -envisioning and understanding anew one’s surroundings and circumstances are invaluable. By bringing together a diversity of voices collectively innovating

art -based approaches, strategies, and perspectives to addressing these issues, this book aims to contribute to this growing public discourse and its related practices.

Four cross -cutting themes flow through the papers: (1) the use and animation of the public realm for (2) public engagement and participation in (3) encouraging change or transition, with a central focus on (4) the role of artists and art practices in this activity and change. The papers are organized into three sections: Artistic Inquiry: Animating Ecologies, Embodying Territory; Community Action: Building Spaces to Engage with Nature; and Public Art: Catalyzing Social Connections and Public Action. All papers focus on illuminating interconnections, so organizing them proved to be a challenging task. As readers will notice, there are complementarities and echoes among the papers and across the sections, as is itting with eforts to link artistic inquiry and action, the use of public spaces, and catalyzing social connections. Each section begins with full essays, followed by a series of shorter proiles of particular projects and approaches, and the insights and relections resulting from them.

Artistic inquiry: Animating ecologies, embodying territory

This section begins with papers on two long -term initiatives from Western Australia and Canada, each examining and engaging with elements of community resiliency, sustainability, and survival. For over 15 years, the Rural Design Studio of Western Australia has explored “the animation of community engagement” through storytelling and performative design in partnership with small agrarian communities. Using “artful processes” to identify and challenge key contemporary issues and valourizing practices of “regenerative chance and indeterminacy,” Ailsa Grieve and Grant Revell explain how the Studio’s activities allow communities to get to know one another, and to develop and seek solutions for social, environmental, and economic survival, sometimes recovered from the past. The Studio works from a perspective of holistic systems and dynamic practices of regenerative thinking to “encourage humans or communities to participate as nature and culture, as opposed to doing things to nature and culture,” through which new aesthetics of cultural sustainability

may be developed. The Studio’s work seeks to activate create processes and give life to otherwise culturally suppressed landscapes, rooted in the importance of self -empowerment. In a context of “an unpredictable (slippery) future,” these processes comprise an art at “the edge of a widening consciousness and a deeper understanding of place.”

Within a small city context, artistic inquiry and university -based artists in the Small Cities Community -University Research Alliance in Kamloops, British Columbia, Canada, have taken lead roles in deining and contributing to community engagement for over 12 years. Relecting on the evolving roles of artist -researchers in this interdisciplinary research initiative, despite challenges in framing the value of the arts within this context, W.F. Garrett -Petts argues for art as a public sphere in which artist -researchers contribute new critical perspectives, new forms of inquiry, and new circumstances useful to creatively animate public spaces. For instance, within the context of interdisciplinary research involving visual artists, artistic inquiry helped redeine traditional modes of research, introducing a “creative destabilization of disciplinary assumptions” in the projects, and inluenced community and cultural change. Outside of a research context, one might extrapolate that the insights, perspectives, processes, and knowledge that artistic inquiry can bring, and the impacts on challenging and extending ‘ways of thinking and working’, can be valuable in community settings searching for new means to tackle issues and design future trajectories of living together. However, as Garrett -Petts warns, the intervention and involvement of artists may catalyze changes in thinking,but without continuing experimentation and self reflection, the creative destabilization efect may not result in longer -term changes in behaviour and practice among non -artistic researchers /participants. Garrett -Petts thus argues the need for continued eforts to construct spaces for the emergence of a new type of visual/ verbal interface, with the aim of developing these collaborative terrains for inquiry, thinking, and acting.

How can artists encourage users of a public space to ‘co -own’ the space toward greater respect and responsibility for the location and other users, ultimately building greater social integration and sustainability? How can public spaces for interaction and engagement be designed that allow for an optimal balance between the artists’ work and the voice of the users/audience of a public space? The experience of the students’ theatre workshop/exchange held in Coimbra, compared with the work of two artist collectives in the Netherlands, inspired critical relections on artistic experiments with public engagement, considering diferent functions of public space, levels of participation, and the balance between the art work and the audience. Nelly van der Geest develops a ‘rolodex’ model that brings these three dimensions together, and maps the experiments

in terms of these axes. From a perspective of fostering social sustainability, the article concludes that for interventions in public space where artists and audiences meet to successfully harmonize the voice of the artist with those of the public space users, the project design must include interventions focusing on the level of participation of the audiences: to move from a mode of ‘enjoyment’ to ‘mutual talk and doing’ to ‘co -design’.

Three artistic perspectives on the interconnections among artistic inquiry, place, and public engagement complement these analyses. Through a photo essay of art works created for the exhibition, “Coimbra C,” at Circulo de Artes Plásticas de Coimbra in 2003, and their original inspirations, António Olaio illustrates how the complex aesthetic experiences of a city like Coimbra can inspire diverse avenues of artistic creation. In turn, artists’ symbolic and abstraction strategies provide new works and images that critique, inform, extend, and potentially transform our ways of understanding the city and its elements.

Donald Lawrence, an artist -researcher within the CURA project in Kamloops, considers the manner in which artistic practice may migrate between the realms of individual and interdisciplinary inquiry. He brings forward the idea of search as a kind of synthesis of research and exploration, a suggestive expansion of the ways in which art expands our awareness of our surroundings. He also highlights the relationship between play and learning: the attribution of a status of ‘play’ to an experience may enable us to bring to the situation our acquired knowledge. For example, in Coimbra a workshop experience using a tent camera obscura to observe one’s surroundings engendered a dimension of play and a luid manner of learning. The experience provided an opportunity to obtain a fresh look at one’s environment “in an exploratory way that echoes essential aspects of artistic and other creative practices” and, potentially, an expanded understanding of the workings of one’s landscape.

Sara Giddens and Simon Jones relect on the experiences of performing an ambulant audio performance carried out in the midst of busy public spaces in diferent cities around the world. Over time, the work increasingly came to focus on how public space articulates local histories with lived memories, and took on the form of a co -design, a dialogue with participants. The paper explores the works’ diferent manifestations and proposes ways in which the artists’ passing through a city can open potential spaces for relection on the everyday use of public space. The artists encourage participant ‘auditor -walkers’ to experience both the sensual immediate and the mental relective, thus embodying the conluence of the practical and the critical in the animation of public space through the arts.

Three brief proiles follow. Charlotte Šunde and Alys Longley discuss an arts -science -education collaboration on water issues in Auckland, New Zealand, in which a series of urban installation/performance works animated elements of the material, technical, social, cultural, spiritual, and economic dimensions of urban waters and waterways. The fluid city project interwove scientific knowledge with artistic methods to evoke, provoke, and prompt new ways of seeing, interpreting, and sensing understandings associated with water. The project took research out to public spaces, with the aim to allow these publicspaces to speak and to create conscious space for thinking and feeling the city diferently. Embracing the element of surprise and creating spaces for personal stories to the articulated and shared, animating public spaces through the arts enabled the creation of “new experiences, ideas, and relationships that may potentially evoke emotional responses and recognition” that water is far more than a physical resource or commodity, and lead participants – as ‘water- -dependent citizens’ – to engage in a new relationship with their urban waters.

Echoing van der Geest’s points about ‘co -owning’ a public space, Javier Fraga Cadórniga describes how Raons Públiques uses art to catalyze public participation in Barcelona, Spain, “encouraging citizen co -responsibility in the use, management, and design” of the public space in order to contribute to more cohesive and sustainable communities. Intervention strategies focus on collecting residents’ sensitive information about the use and perception of a space and using diferent tools to “spark debate, encourage dialogue, and start encounters that awaken relection” (e.g., tea or cofee gatherings for elders to Public Space Trading Cards for children). In such contexts, the arts and art -related processes can play a key role in transforming public space into “an essential element of social cohesion” in society, stimulating chance meetings but also creating new necessary relationships. Further, the processes animated by these various interventions can help communities “to build together their own space and its management, so that they make it theirs and take on both its physical and abstract meanings.” The collective awareness of the public space

engenders attitudes to help these environments be sustainable.

Emma Arnold relects on the internationally proliferating phenomena of textile graiti as a form of public art from a sustainability perspective, highlighting its ideological and intangible contributions to creating awareness and connection with urban spaces, which is important in fostering environmental awareness and responsibility. Crafted products create a “feminization of space” and may be employed publicly to help create awareness of speciic social, environmental, or economic issues. More broadly, the craft and handmade movement counters large -scale industrial modes of production and consumption, reconnecting individuals to more responsible and sustainable forms of consumption, and revolves around ideas of participation, collaboration, connectivity, collectivity, inclusion, and community – a movement that the handmade aesthetic of textile graiti may publically encourage and popularize.

Community action: Building spaces to engage with nature

Agriculture has been a basic and vital human activity on which much social life been based. In the light of contemporary society’s largely de -humanized and mechanized process of food production, and a generally weak attachment of urban dwellers to natural processes and food sources, a rapidly growing interest in and engagement with gardens, gardening, and agriculture can be seen proliferating around the world. Giovanni Allegretti, Stefania Barca, and Lúcia Fernandes explore the rise of agricultural gardens in urban areas and the neo -rural transition movement, viewing urban farming as a form of ‘popular art/craft’ through which individuals and collectivities re -connect with nature while also re -inventing social connections at the community level. They point out that while the underlying motivations for these activities vary widely, they are being broadly encouraged by an international urban imaginary involving an array of developments, from ‘urban icons’ of integrated gardens and green walls in new architectural developments, to new parks like New York’s High Line, to farming simulation video games and ‘didactic farms’, to a growing array of mass market products and technological innovations to enable urban inhabitants to “celebrate small rituals of a ‘return to nature’ in their own private or semi -public spaces.” Cultural institutions like museums and information -sharing initiatives strive to expand public knowledge and critical relection about such practices beyond ‘mere fashion’, while artists, architects, and designers often play catalyzing roles in promoting this recent wave of institutional programs and grassroots practices, reintroducing food production and greenery into urban spaces, and transforming them into community -tended spaces.

Robin Reid, Kendra Besanger, and Bonnie Klohn discuss the creation of a public produce garden in an empty lot in the city centre. Public produce gardens are developed as sites of collaboration and dialogue around local food production and urban spaces, and produce free produce that any member of the public may use. The Kamloops Public Produce Project, as with many urban agricultural projects, draws on members’ knowledge and practices of the past and can be seen as “creative, grassroots responses to less than ideal social, economic, and environmental circumstances.” As a catalyst for change, the project aims to inluence local food policy and to widen “acceptable” urban agricultural practices. It incorporates “artistic interjections” to contribute to its allure as an accessible public space and to socially function as a place where communities can tell their stories, build creative capacity, address social agendas, expressidentity, and participate directly in the development of their own culture(s).

Focusing on individual impact, Annelieke van der Sluijs discusses how, through participative processes, Coimbra residents are empowered to implement sustainable behaviour change in their daily lives, supported by a local “food web and community.” Echoing Lawrence’s emphasis on play as a learning enabler, van der Sluijs notes, “if it is not fun, it is not sustainable.” Solutions need to be practical as well as attractive to be adopted and to touch upon creative impulses in participants, thus enabling personal connection with the aesthetic values of gardens.

Tania Leimbach describes a ‘meanwhile’ project showcasing green walls on the temporary hoardings surrounding a construction site in Sydney, Australia, and promoting the importance of localized food systems, urban agriculture, and systems thinking in the development of sustainable futures. By introducing an unexpected element into the daily routine, the project aimed to contribute to cultural change by stimulating thinking and inspiring action about introducing new ‘green’ possibilities and imaginaries into the urban environment.

Creating spaces for reconnecting with nature, on a local scale and more broadly, is also the imperative behind public art projects such as Walkway in the Loire estuary in France and more large -scale initiatives like the Spacefor Life complex in Montreal, Canada. Inspired by her experiences assisting in the construction of Walkway, Catalina Trujillo relects on her connection to the quiet existence and vulnerability of nature surrounded by industrial sites. The construction of an observatory tower and extended walkway was a collective exercise involving local residents and as well as visiting students who were hosted in the village. The tangible process of construction became a collective memory, and the resulting art work enables humans to directly experience the wetlands anew, forming a place to seek harmony and a passage to quiet change.

‘Space for Life’ in Montreal, to be Canada’s largest natural sciences museum complex, aims to bring humankind closer to the natural world. Rooted in the importance of biodiversity to our collective survival and guided by a scientiic and artistic approach, Charles Mathieu Brunelle describes how four major science institutions are being brought together to urge visitors to rethink and strengthen their bonds with nature, and to invite them to cultivate a new way ofliving. Similar to the luid city project (Šunde and Longley), an array of modes of “informed contact” will teach people through experiences, including immersive, festive, and entertaining ones.

Public art: Catalyzing social connections and public action

Public art initiatives are highly varied – they may encompass visual/sculptural installations, performances and performative actions, or may lie in the design and generation of social exchanges and processes to build capacities and strengthen connections within communities. Art in public space must attract attention and reach an audience within spaces dominated by the “functionalities of everyday life” and the “strict attention economy of the city” (Jespersen). This section examines the impacts of an array of art projects in the public realm from the perspective of artistic strategies of public engagement and assessments of public reception. These explorations and analyses form a valuable critique to the prospective roles of arts activities in encouraging social change toward more sustainable communities.

Line Marie Bruun Jespersen examines the meeting between contemporary art, the public, the urban realm as a context for art experiences, and the viewers. Focusing on the relationship between two art works of Jeppe Hein and their viewers/users, she highlights how elements of playfulness, humour, and direct participation are used to generate social situations where meetings between strangers and cultural exchange can take place. She asks: Can such art contribute to the creation of a diverse, well -functioning public domain? Can art in public space actually connect people? She brings forward key concepts of relational aesthetics and collective reception to investigate this question. In the cases examined, the physical object functions as the mediator for an experience, but diferent aspects of the same work can relate to diferent experience types. While not arguing that art should be used to create new public domains, she inds that art can inspire and explore how to create inviting spaces that appeal to a broad variety of audiences. Art works can create meeting places, ‘social interstices’, alternative types of spaces freed from consumer discourse. An unusual experience with a group of strangers can generate communication or at least raised awareness of the other(s) in the city. Art can invite broad audiences to perform socially, together.

Some limitations of invited social performance are explored by James Hofman, who relects on the reception of an interventionist artistic performance of community action in a small city. Community groups involved in The REDress Project aimed to ameliorate or eradicate a troubling social situation: 600 missing or murdered Aboriginal women in Canada over the past decades. While the project as a social endeavour was valuable and necessary, and the goals of efective social change were possible, Hofman found the project’sreduced impact was due to the limitations of the artistic genre itself. As an art work intended to foment social change, the development of social exchange was limited, with participants positioned mainly as observers and listeners. Comments during the site tours and panels tended to lean toward feelings of uncertainty and helplessness rather than concrete solutions or plans. Hofman’s insights comment on the dimensions of staging of public participation and the channelling of public voices into and beyond such works in order to generate ongoing change beyond awareness raising.

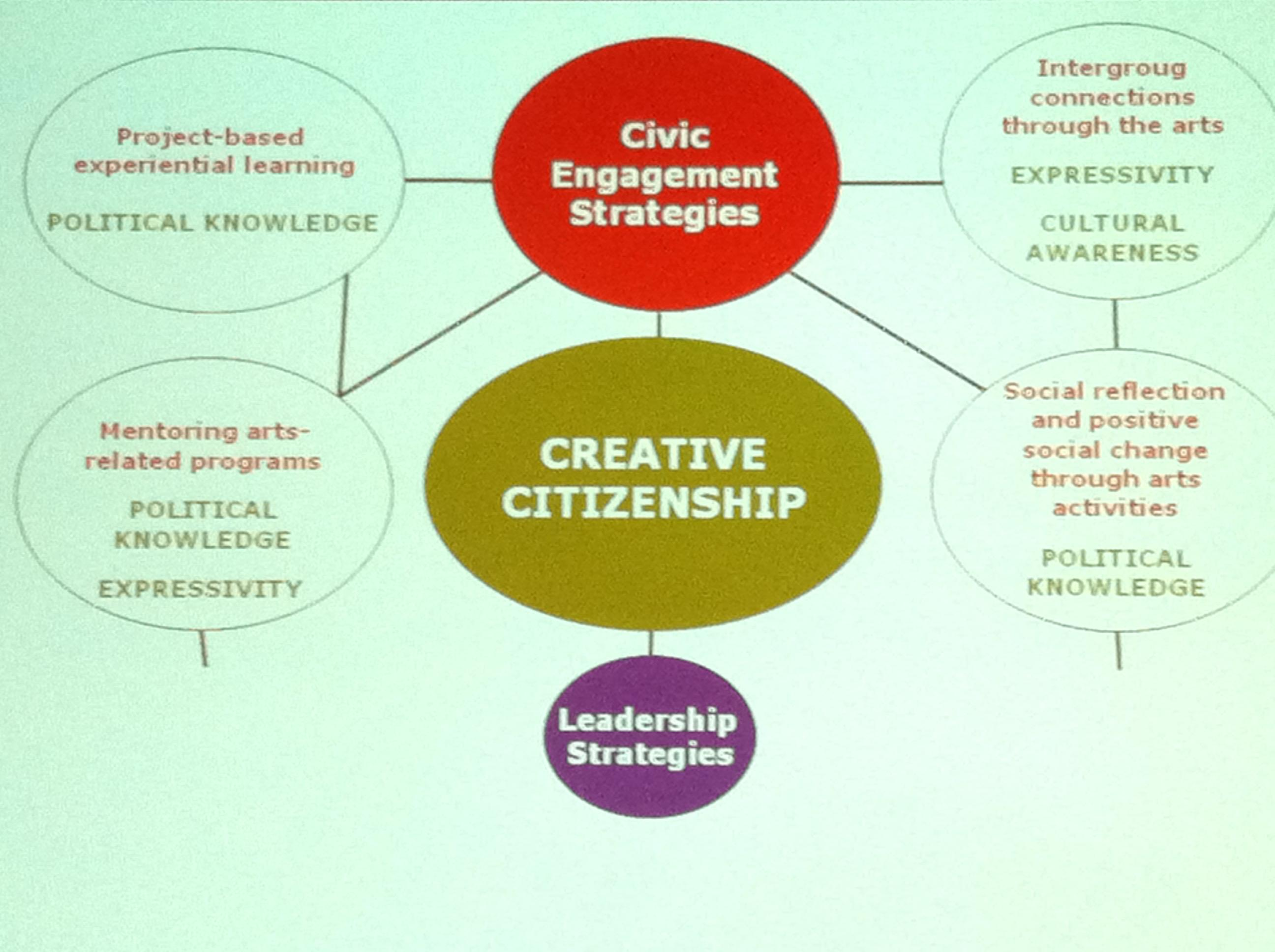

With a focus on communities of youth, Claudia Carvalho explores the interconnection of arts and culture, urban public space, and community as a platform to revivify urban space and to re -address citizenship at the community level. Artistic eforts and strategies of civic engagement and leadership in these communities encourage the production of creative citizens. In turn, the appropriation of creative citizenship provides personal and collective avenues for developing and advancing attachments to place, intercultural dialogue, and local development and sustainability. Examining three case studies in Boston, Carvalho identiies three stages in the process of citizenship building at the community level: identifying the main community actors in the local context and the kinds of associations possible; building and reinforcing a community identity in diferentiation to others; and creating collective actions involving ethnically and socially diverse communities, which interact to build a shared, place -based community identity. In all phases, artistic activities are tools of outreach to community members, and all community members are understood to be potential agents and active citizens. In these situations, artistic practice was an “indispensable learning tool in promoting self -empowerment” for the development of creative citizens actively engaged in improving their local community and its urban space.

A similar theme resonates within Melinda Spooner’s proile of the Illuminate project in Halifax, Canada, which also aimed to empower youth. It used art programming and mentorship to forge connections among diverse population groups, enhance community vitality, and catalyze ongoing connections and additional projects.

In many places, the development of more socio -culturally sustainable and resilient communities involves addressing and dismantling post -colonial legacies, constructing new stories, and building for the future on renewed foundations. Toward this end, and in the context of artistic objects as transgressive and active dissenters, Paulo Pousada provides an investigation of the contemporary art works of Ângela Ferreira. Ferreira’s gaze on and critique of built artefacts and public spaces of colonialism have contributed to greater critical awareness and opened up questioning about processes of remembrances, nostalgia, and “given history.” Pousada highlights how the transgressive functions of art to perceive social contradictions and “cultural bashings” (and to expose underlying political and socio -cultural currents that propel these occurrences and trajectories), make it a prime instrument to expose and ight the naturalization of injustice and to disclose and deplore the “unspoken prejudices and fears embodied in everyday protocols of human and community relations” – all essential processes in examining, rethinking, and reimaging our societies.

Alix Pierre and Simone Pierre’s proile paper highlights the importance of community -engaged artistic processes and community celebration in the large -scale public commemoration activities of the 150th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation in Guadeloupe. Within this context, the Civic Edupreneurship and the City program centred on creative ways the city could engage its constituents – especially the youth – in “(re)claiming their historical past to better negotiate the present.” In joining the commemorative efort, students left their schools and “laid claim to the city landscape.” More importantly, the project aimed to provide young Guadeloupeans an opportunity “to critically envision themselves in their relation to the world.”

In Stories from HOME, an art -research intervention in a social housing estate near Melbourne, Australia, artist -researchers Marnie Badham and James Oliver developed a situated arts -based and ethnographic methodological approach to participatory and generative research with vulnerable communities. Aiming to challenge representations of place -based stigma through a community -based art practice, the artist -researchers employed a participatory/advocacy approach in which artistic inquiry was intertwined with an agenda to increase the social and political self -empowerment of that community. Focused on “the relational qualities of process -driven practice,” the project generated dialogue through the

process of participatory art -making, created a platform for coming together and creating bonds, facilitated dialogue among diverse residents, and re -animated their shared space.

As Francesa Rayner relates, the Maria Matos theatre company in Lisbon promoted two initiatives that transformed public space and created venues for social interaction, anchored around themes of particular social tension – respectively, (non)abundance and the impact of austerity measures in Portugal. In these initiatives, audiences were treated as empowered and active social agents. Transforming audiences into participants, Rayner contends, is a vital part of “extending cultural citizenship.” Further, she argues that forms of “non -directed social encounter outside conventional theatre routines” based on experiment and informal discussion can promote more socially aware, integrated local sustainability in which artistic, social, and environmental aspects of sustainability are raised simultaneously rather than separately.

Similar non -directed social encounter was a key element of Petra Johnson’s kioskxiaomaibu site -speciic art project, which involved setting up kiosks in Cologne, Germany, and Shanghai, China, and linking them via Skype, with kiosk proprietors and customers invited to make use of the platform as they wished. The kiosks were conceived as venues for artistic explorations, and as platforms for unmediated connectivity. Over a six -month period, the practice emerging from the experience was one of setting a stage and then, in a subtle and disciplined manner, retreating, allowing a multitude of people to exchange perspectives, questions, and details of their daily lives.

From the perspective of ‘inding hospitality’ for critical ideas in a relevant part of the public domain, the notions of collaboration and exchange become central. In When Guests Become Host, a public art research project investigating artistic strategies, artist -curator Danielle van Zuijlen invited two artist collectives (from Austria and the United Kingdom) and an architecture collective (from Latin America) to develop new work in the public domain of the city of Porto. The strategies greatly diverged, depending on the aim of the intervention, from a formal and political strategy; to a largely informal strategy to mobilize the memory, imagination, and commitment of local people; to an almost activist approach. Each approach cultivated relevant collaborative arrangements with local residents and organizations, ‘found hospitality’, and produced hospitable

gestures in return.

Finally, focusing on the legacies of ephemeral experiences that live on in spectator memories, Jochem Naafs describes how community -based Stut Theatre, based in Utrecht, The Netherlands, aims to (re)create and sustain a ‘community of spectators’. Through creating imaginative, socially engaged experiences rooted in the stories of speciic communities, it has developed an ever -growing array of communities with which it has worked, whose members come to subsequent shows in other areas. Through its work, the company aims to foster dialogue that begins in the theatre and continues after the live show, to stimulate an “active remembering” and a sustainable public discourse based on the experience.

Altogether, the collection provides a rich array of practice -based insights and knowledge based on artistic interventions to engage publics as active collaborators; to animate public spaces to foster encounter, dialogue, and social cohesion; and to build individual and collective capacities and renewed foundations from which to build forward. From the perspective of developing more culturally, socially, economically, and environmentally sustainable and resilient communities and cities, arts practices can play key roles in a numberof dimensions: arts -based activities and interventions can activate public engagement, catalyze social relations, and evolve new ways of working and living;

they can physically and symbolically change the spaces in which we live and relate, and foster greater connections with our natural and built environments; and they can provide new ways of perceiving and inquiring about the world, provoking and fostering changes in thinking, acting, and living together.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to António Olaio for information about ‘Semana da arte na rua’ and to Circulo de Artes Plásticas de Coimbra (CAPC) for use of images from this event.

References

Choe, S. -C., Marcotullio, P.J., & Piracha, A.L. (2007). Approaches to cultural indicators. In M. Nadarajah & A.T. Yamamoto (eds.), Urban crisis: Culture and the sustainability of cities (pp. 193 -213). Tokyo: UNU Press.

Duxbury, N., Cullen, C., & Pascual, J. (2012). Cities, culture and sustainable development. In H.K. Anheier, Y.R. Isar, & M. Hoelscher (eds.), Cultural policy and governance in a new metropolitan age (pp. 73 -86). The Cultures and Globalization Series, Vol. 5. London: Sage.

Duxbury, N., & Jeannotte, M.S. (2012). Including culture in sustainability: An assessment of Canada’s Integrated Community Sustainability Plans. International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development, 4(1), 1 -19.

Hawkes, J. (2001). The fourth pillar of sustainability: Culture’s essential role in public planning. Melbourne: Common Ground.

UNESCO. (2013). The Hangzhou Declaration: Placing culture at the heart of sustainable development policies. Paris: UNESCO. Adopted in Hangzhou, People’s Republic of China, on May 17, 2013.

United Cities and Local Governments (UCLG). (2010). Culture: The fourth pillar of sustainable development. Policy Statement, adopted in Mexico City on November 17, 2010.

Williams, K. (2010). Sustainable cities: Research and practice challenges. International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development, 1(1), 128 -133.